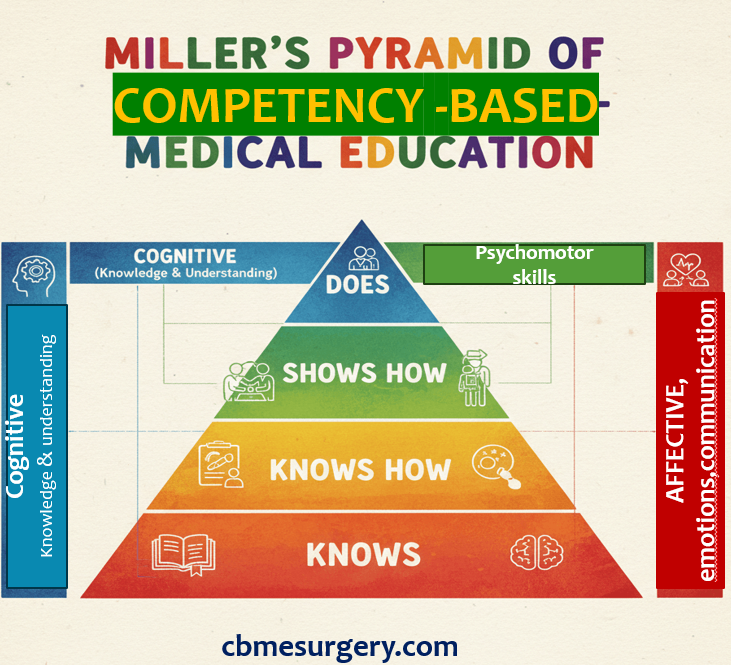

Millerʼs Pyramid and Competency-Based Surgical Education

Surgical training has shifted significantly from traditional time-based models to a competency

based framework. This modern approach prioritizes outcomes, integrated abilities, and practical

application to ensure trainees can deliver safe, effective, and holistic patient care. At the heart of

this evolution is Miller’s Pyramid of Clinical Competence, a model essential for guiding the

assessment and development of clinical skills.

Core Domains in Surgical Training

Modern surgical education is built upon three primary domains to ensure a well-rounded skillset:

1. Cognitive Domain

Involves acquiring foundational knowledge through lectures and self-directed study.

Focuses on anatomy, physiology, pathology, and surgical principles needed for decision

making.

2. Psychomotor Domain

Centers on physical skills such as suturing and laparoscopy.

Utilizes simulation training to build technical proficiency in a safe, controlled environment.

3. Affective Domain

Highlights non-technical skills including communication, teamwork, and professionalism.

Addresses the fact that surgical complications often stem from non-technical errors rather

than lack of manual skill

Domain | Focus | How to learn & Develop |

Cognitive Domain (Knowledge) | Factual knowledge, foundational scientific principles, and subject-wise outcomes | Engage in lectures, reading, and self-directed learning. Focus on deep understanding rather than just memorization. |

Psychomotor Domain (Skills) | Physical skills, procedures, and practical application | Focus on psychomotor skill development and simulation training. Practice technical skills repeatedly in controlled environments (e.g., simulation labs). |

Affective Domain (Attitude, Ethics, Communication) | Proper attitude, professionalism, ethical behaviour, and communication skills. | Participate actively in the Attitude, Ethics, and Communication Module (AETCOM). Engage in role play and group discussions, focusing on elements like doctor-patient relationship building and understanding patient perspectives. |

- Structuring Your Learning with Miller’s Pyramid

Miller’s Pyramid (1990) provides an excellent framework for ranking clinical competence, moving from theoretical knowledge at the base to clinical action at the apex. It dictates that for true competence, you must be assessed in the setting where you are expected to perform.

Level 1: Knows (Accumulation of Expert Knowledge)

This is the base of the pyramid, focusing on recalling facts and foundational scientific principles (e.g., anatomy, physiology, pathology).

- Learning Focus: Understanding core surgical concepts (e.g., anatomical relationships, disease processes, indications for surgery).

- Study Methods: Reading textbooks, attending lectures, and self-quizzing to acquire expert knowledge.

Level 2: Knows How (Knowledge about Theoretical Application)

This level requires the ability to apply and interpret knowledge, understanding the relationships between concepts and principles. This is applied knowledge or conceptual competence.

- Learning Focus: Understanding why and how procedures are done, and knowing what to do if complications arise. Learning algorithms, interpreting lab results, and formulating differential diagnoses.

- Study Methods: Working through case studies, writing essays, reviewing clinical algorithms, and engaging in problem-solving exercises.

Level 3: Shows How (Application in Practical Scenarios)

This level requires demonstrating your skills in a standardized, structured environment constructed specifically for assessment. This is often achieved in simulation settings.

- Learning Focus: Practicing basic clinical skills, surgical procedures (e.g., suturing, knot tying), and communication techniques.

- Study Methods: Participating in simulation (mannequin-based, virtual reality, procedural task trainers) and role-play exercises to apply knowledge in practical scenarios. Practicing communication skills using frameworks like the Kalamazoo Consensus Statement elements (e.g., building the doctor-patient relationship, sharing information, providing closure).

Level 4: Does (Application in Real Practice Situations)

This is the pinnacle of the original pyramid: performance in the workplace during the natural workflow. It reflects the routine application of knowledge and skills in the clinical setting.

- Learning Focus: Translating your learned knowledge and demonstrated skills into independent, safe patient care. This requires professionalism, motivation, and applying skills continuously in the real environment.

- Study Methods: Work-based placements and direct observation during actual patient care. Seek out timely feedback from your clinical supervisor after each patient encounter or teaching session.

- Integrating Core Competencies through Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs)

The shift in surgical training moves away from relying solely on time or case numbers to a holistic review of your performance across all core competencies. This is operationalized through Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs).

EPAs are defined as tasks or responsibilities that you are expected to perform once you have achieved sufficient competence. They translate general competencies (like Patient Care and Professionalism) into executable, observable, and measurable units of professional practice.

For surgery, examples of EPAs include the evaluation and management of conditions like inguinal hernia, gallbladder disease, or acute abdomen.

How to learn via EPAs (The Entrustment Progression):

- Focus on Milestones: EPAs are broken down into progressive milestones, which are the expected abilities at different stages of your training. For example, the EPA “Gather a history and perform a physical examination” is tied to milestones specific to the end of Year 2, Year 3, etc..

- Practice for Entrustment: Your ultimate goal is to be fully “Entrustable”—meaning you can perform the activity without direct supervision by the time you graduate.

- Develop Adaptive Expertise: Entrustment decisions encompass more than just observed performance; they imply confidence that you can handle unexpected challenges and unknown future situations. Strive to understand the risks involved in clinical care and demonstrate the ability to ask for help when necessary (help-seeking behaviors).

- Preparing for Assessment using Miller’s Hierarchy

Assessment in CBME uses multiple measures to evaluate you in diverse settings. You must adapt your study methods to match the Miller level being tested:

Miller Level | Focus of Assessment | Assessment Methods to Prepare For |

Knows | Factual Recall/Foundational Knowledge | Written Exams (MCQs, short answer questions) and online quizzes. |

Knows How | Interpretation/Application/Clinical Reasoning | Written or Oral Tests featuring problem-solving approaches, case-based questions, and analysis of clinical data |

Shows How (Performance in Simulation) | Demonstration of skills in a standardized environment | Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) and Objective Structured Practical Examination (OSPE). Practice procedures and structured communication exercises, often involving standardized patients or mannequins. |

Does (Performance in Practice) | Routine, unsupervised application in the real world | Workplace-Based Assessment (WPBA) such as mini-CEX (mini clinical evaluation exercise), Direct Observation of Procedural Skills (DOPS), logbooks, and multi-source feedback (360° feedback). Focus on consistent, honest, communicative, and professional behavior. |

Important Note on Assessment Validity: Assessments that rely on demonstration or performance in the workplace (Shows How and Does) are generally considered more valid measures of professional life than written exams. Therefore, dedicating time to rigorous clinical practice and actively seeking feedback are the best ways to prepare for high-stakes clinical assessment.

In summary, surgical learning under CBME is holistic and continuous. By aligning your learning goals with the progression defined by Miller’s Pyramid—from foundational Knowledge to applied Skills to demonstrated Action (Does)—and focusing on the integrated demands of EPAs, you will be well-equipped to meet the global standards required of a modern Indian medical graduate.